"The myth of the ‘dark ages’ is still alive and kicking unfortunately."

Interview: Dr Shazia Jagot on Chaucer, Astrolabes and Persian Polymaths.

Dr Shazia Jagot is Senior Lecturer in Medieval and Global Literature at the University of York. Her research focuses on cultural and intellectual interaction between the Islamic world and Medieval Europe. She holds a PhD from the University of Leicester and has worked in Jordon, Denmark, and the UK.

What first inspired your interest in medieval history and literature?

Reading Middle English poetry during my undergraduate degree. This was the first time I had encountered medieval literature and its difficulties and intricacies, but it was the figure of the ‘Saracen’ and representations of the ‘East’ that really caught my attention. And that, in a roundabout way, inspired me to take up an MA in Near and Middle Eastern Studies which is when I was completely captivated by the history of the premodern Islamic world.

What is the most common misconception you encounter about the medieval period?

That nothing happened! The myth of the ‘dark ages’ is still alive and kicking unfortunately.

Your research explores Arabic influences in Geoffrey Chaucer’s work. Can you tell us a little about this?

Chaucer is a fascinating multilingual poet and we know that he engaged with literature from different languages and traditions, in particular Italian, French, and Latin. For a long time, scholars have also recognized that Arabic science had influence him, especially in his unfinished prose Treatise on an Astrolabe (the more serious of his writings!) but there was little appetite or expertise to dig much deeper. I aim to do this digging! I’ve found there’s so much more to this – scientific, philosophic, and literary writings that were developed in the Arabic-Islamic world and were sought after by scholars in Latin Christendom, also interested laymen like Chaucer (who was a curious man!). He name-drops Arabic and Persian polymaths, he engages with Latin translations of Arabic scientific material, he uses Arabic vocabulary as he is curating Middle English as a language of poetry, and he shows us both an imagined representation of the ‘East’ and familiarity with the core tenets of Islam.

Do you have a favourite historical source, document or artefact?

Right now, I am a little obsessed with medieval astrolabes. I don’t have a favourite one because there are so many! Astrolabes are circular scientific instruments, usually made of brass that can be held in your hand. They provide a stereographic projection of the universe and were used for a variety of astronomical calculations, like charting the course of the sun and the moon, calculating the time of day, the length of a shadow, the positions of the stars. As objects, they are full of splendor with precise engravings, star names, and sometimes even zoomorphic or vegetal images in the star maps. Each one is unique yet they are also ubiquitous – fascinating!

Do you have a fixed research process, or does it change depending on the subject?

It changes depending on the subject and also time restraints. I often liken what I do to being an interdisciplinary literary archaeologist – for my work on Chaucer, I start with a small detail and then begin an excavation through a variety of sources that takes me through Middle English, Latin, sometimes French, and Arabic. These are usually sources from different disciplines too which will often take me into the study of optics or astronomy or natural philosophy.

What’s the best advice you have ever been given?

I have two! 1) It doesn’t need to be perfect, just finished. And, 2) that it’s okay to say ‘no’ because it means you’re saying ‘yes’ for other priorities.

What’s the last great history book you read?

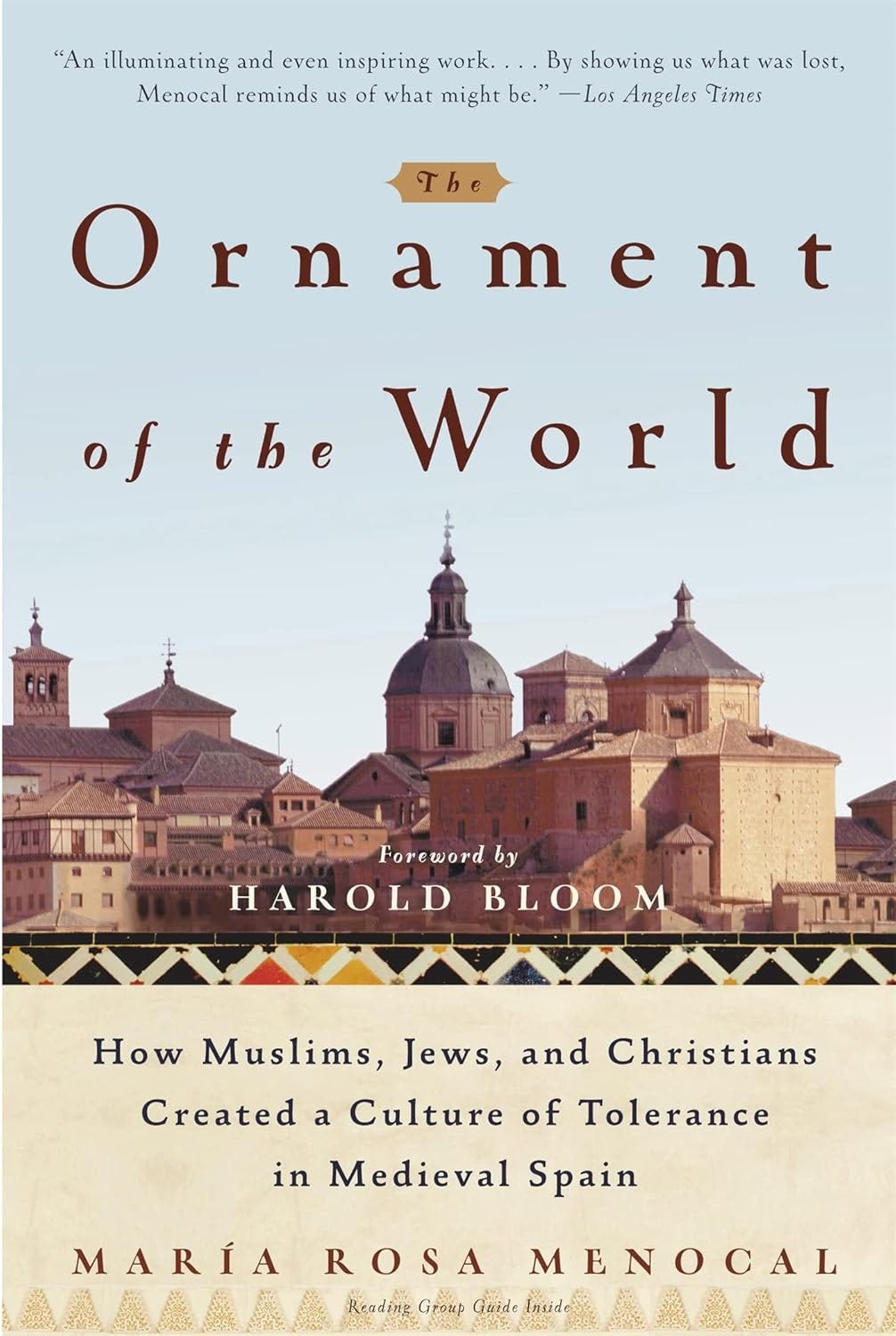

I’ve just re-read Maria Rosa Menocal’s The Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews, and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain. Menocal was a historian of medieval Iberia and she wrote a number of accessible paradigm-shifting books. The Ornament of the World was published in 2002 and is still so relevant today – it brings to life al-Andalus, the name given to Muslim Spain, and shows how it flourished and then withered (the last stronghold of al-Andalus, Nasrid Granada was taken in 1492 by Isabella and Ferdinand of Castile). It initiated and opened up so many pathways for understanding the lives of religious communities, Jewish and Christian, the languages and literary traditions used and spoken, especially Arabic and Hebrew. This re-read made me appreciate Menocal’s framing of Europe too – this is history where Islam is in Europe and cultivated and nourished European culture.

If you could travel back in time for 24 hours, where and when would you go and why?

I would love to go back to the late tenth century and experience a day as a noble woman in Cordoba. I’d especially like to see the palace complex built by the caliph Abd al-Rahman III known as Madinat al-Zahra. This is an archaeological site now, with very little left. It was ransacked in 1009. All accounts suggest that it was a glorious complex that housed administrative buildings, a presidential palace, houses, courtyards with outdoor pools, lush gardens, a mosque for Friday prayers, an extraordinary library, and a spectacular reception hall with a gold and silver roof. It’s also a period of activity for women intellectuals, such as Lubna of Cordoba who is known to be a poet and mathematician. We have very little historical record of women in al-Andalus compared to male figures, and the little we do have suggests that lots of women flourished intellectually and a number of them were fierce and bold poets! It would be a real thrill and pleasure to sit in a salon led by women and listen to them spit satirical and biting verses about life and love.