"I had a wonderful history teacher who used to lean against the front of her desk and teach history as if she were telling us a story"

Interview: historian, literature scholar and author, Leah Redmond Chang on writing, research and her latest book, Young Queens.

Leah Redmond Chang is a historian and writer, who is interested in women and power. She is the author of numerous books, including Portraits of the Queen Mother: Polemics, Panegyrics, Letters, and Into Print: The Production of Female Authorship in Early Modern France.

In February, we selected Redmond Chang’s critically acclaimed multi-biography Young Queens: The Intertwined Lives of Catherine de’ Medici, Elisabeth de Valois, and Mary, Queen of Scots (2023) as our nonfiction book club title. It is no understatement to say the book was a huge hit with book club readers.

What first inspired your interest in history?

I became interested in history thanks to historical fiction. As a child, I loved stories, and I loved to read. I fell in love with a particular series that was very popular among American children: The Little House books by Laura Ingalls Wilder. Those books are historical fiction but based on the 19th-century life of the real Laura Ingalls Wilder, so I thought I was reading history. Those books made me curious about how people lived in the past. Then, in secondary school, I had a wonderful history teacher who used to lean against the front of her desk and teach history as if she were telling us a story. That’s when I started to think of history as narrative.

How did you first encounter the three queens?

I’ve worked on Catherine de’ Medici for a long time, over ten years. As a scholar, I specialized in 16th-century France – if that’s your specialty, you cannot avoid Catherine! I first encountered Elisabeth de Valois while I was working on a scholarly translation and study of works related to Catherine. I remember being quite surprised, in fact, by how little I knew about Elisabeth. As for Mary, Queen of Scots, I began reading about her as a child. But I hadn’t understood how intertwined she was with Catherine de’ Medici and Elisabeth de Valois until I began working on Young Queens.

How important were they in shaping European politics in the 16th century?

They all played important roles in shaping European politics, but some aspects of their influence were more visible than others. Since Catherine was the power behind the throne of France for decades, she shaped policy overtly. Elisabeth de Valois was an important but much quieter political influence. As the queen consort of Spain, she didn’t seem to shape policy directly, but there can be no doubt that she had Philip II’s ear, especially as she grew older. Had she survived past twenty-two, I suspect she would have exerted tremendous influence over Philip II. Which is exactly what Catherine de’ Medici was hoping for.

It is hard to condense Mary, Queen of Scots’s influence on European politics into a few sentences. Let’s just say that, from the time she was born, her very existence was a factor in how kings imagined the growth and shape of their empires. Because Mary was the sovereign queen of Scotland, she was seen from infancy as a marriage prize. English and French kings waged wars to secure her in marriage to their heirs. So, she was very important, although it’s worth noting that during her childhood she didn’t actively shape European politics. Rather she was a political pawn, used by others.

What sources were you able to draw from?

I worked in several different archives in England, France, Scotland, Spain, and Italy, as well as in the United States. I drew from manuscript letters and documents as well as printed primary sources from the 16th and 17th-centuries. I am also indebted to the work of 19th-century scholars who collected thousands of letters from across Europe, and transcribed and published them. I couldn’t have written Young Queens without those fantastic collections.

Do you have a fixed research process, or does it change depending on the subject?

It changes depending on the subject, but there are a few patterns. Although I work in history, I tend to think of my subjects as stories, albeit non-fiction ones. I start by doing some basic research with secondary sources to understand the historical context and then move to primary-source documents as quickly as possible. At a certain point, I figure out the story I’m trying to tell. Then I try to follow my research leads in the direction that the story wants to go.

What’s the best advice you have ever been given?

Writing doesn’t happen through brilliance or inspiration, but rather through consistent hard work. In other words, keep your butt in the chair.

What’s the last great history book you read?

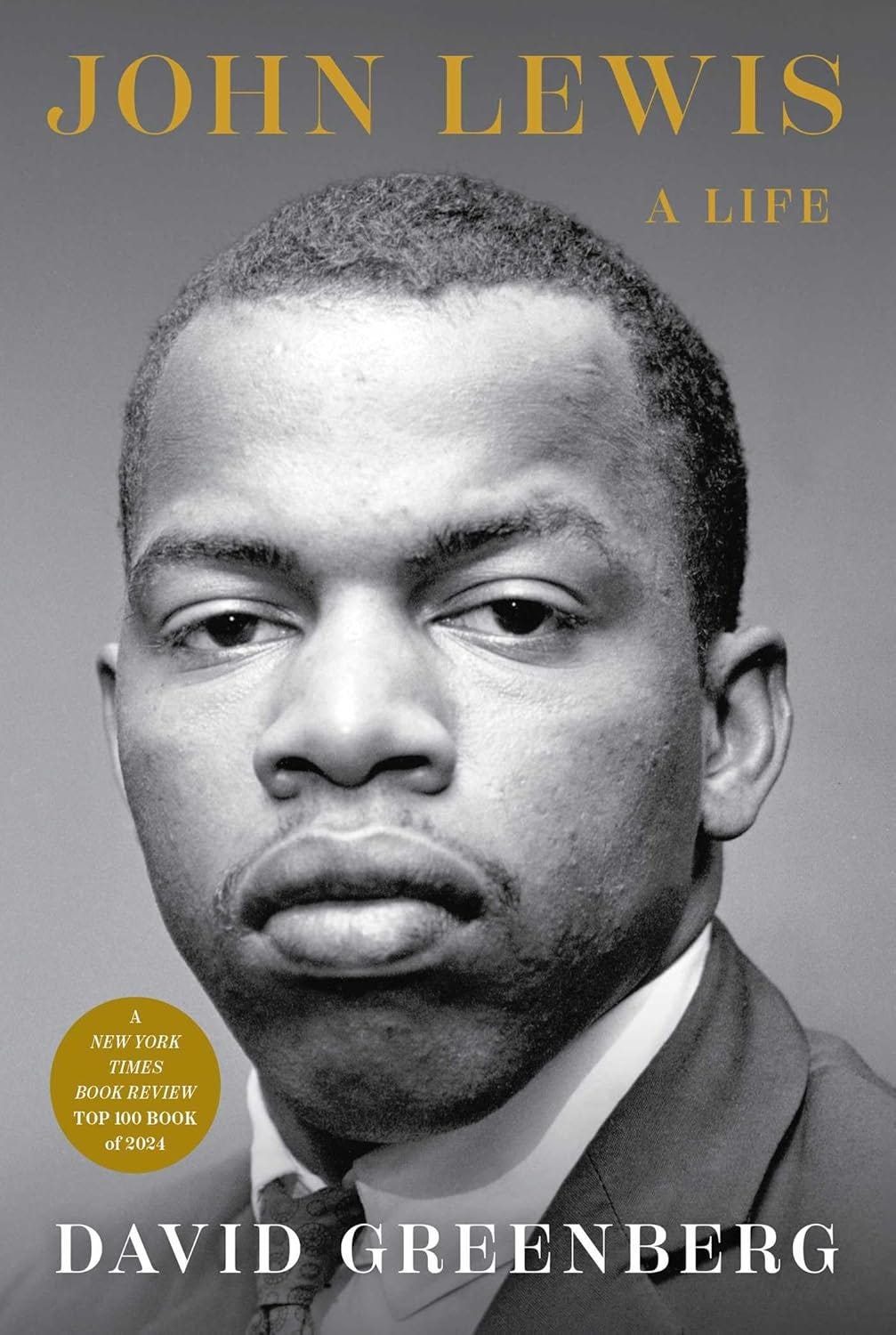

I am just now finishing a brilliant and eminently readable biography of the American civil rights leader, John Lewis, by David Greenberg.

If you could travel back in time for 24 hours, where and when would you go and why?

Do I have to choose only one? That’s a lot of pressure. Ok – keeping to the historical context of Young Queens, I’d want to go back to 1559 Paris, when Henry II of France was mortally wounded while jousting. Historians have never understood what exactly happened there; they know only that somehow a splinter of wood from the lance lodged into Henry’s head. Did the king forget to pull down his visor on his helmet? Was there a screw that came loose so the visor didn’t close properly? Did the helmet not fit correctly? Something like a loose screw seems so inconsequential, and yet that small mishap ultimately led to King Henry’s death. And Henry’s death radically shifted politics in France and across Europe, thrusting the three queens of my book into the spotlight. I would really like to know what happened with that helmet!